Page Title goes here

Provide a short description of your web page here, using bright bold pre-styled fonts with colors that stand out ... to quickly attract the attention of your visitors.

Recent Hawaiian Airlines Article

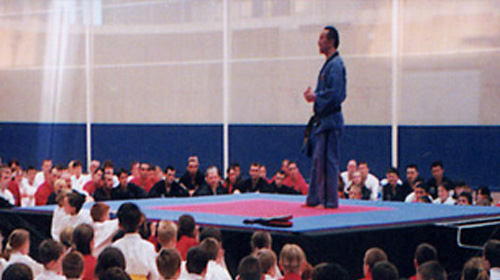

Grandmaster Flash

Koko Marina Shopping Center’s Tae Kwon Do Center is a very noisy place right now. The nearly two-dozen three- to six-year-olds in the martial arts studio’s Panther class are doing drills, and their kicks, blocks and punches are delivered to the staccato rhythm of “I-LOVE-TAE-KWON-DO!” and “I-LOVE-MOM-AND- I-LOVE-DAD!” Earlier, they did their stretching exercises while singing the ABCs.

There are a lot of punches and affirmations thrown about over the course of the forty-five-minute class. But undoubtedly the biggest noisemaker in the 8,000-square-foot studio is Grandmaster Hee Il Cho, the center’s enthusiastic sixty-eight-year-old founder and head instructor. In addition to his booming, gravelly voice that bounces off the studio’s mirrored walls, Cho—equal parts Mr. Miyagi and Sergeant Rock—punctuates his instructions by slapping together two large arm pads normally used during striking drills. The resulting sound is as loud as a thunderclap, but the children, some of them barely out of their toddler years, don’t even flinch (unlike a few parents in attendance). The kids are too busy loving their tae kwon do.

“Teaching children this young is a difficult task,” says Cho. “At this age, it’s much like preschool, where they learn how to be separated from their parents and be comfortable in a strange situation. They come to the studio. They run. They exercise and have fun. I try to play with them and show the kids a little affection early on—before we start and I get strict. That way they know I support and like them and I’m not trying to be mean.”

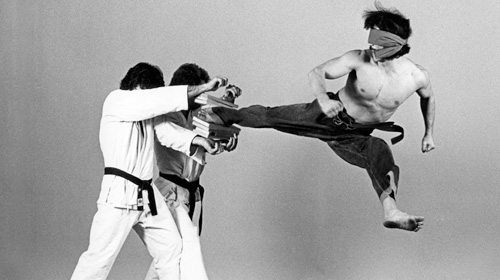

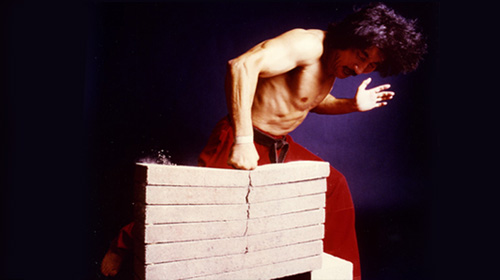

Cho, still well-muscled and pretzel flexible in his seventh decade, is a martial arts icon. He is a master of tae kwon do, the Korean martial art renowned for its powerful striking and acrobatic kicks.

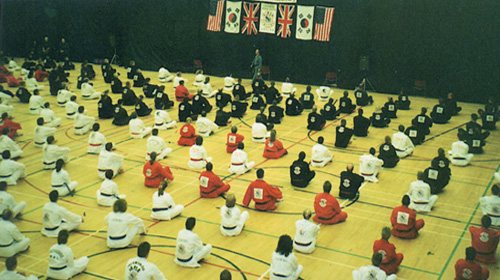

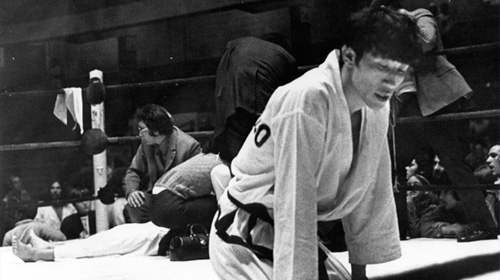

A ninth-degree black belt, he’s won more than thirty national and international tournaments, been inducted into just about every martial arts hall of fame on the planet and has also starred in four Hollywood movies, playing a martial arts competition judge in two films (Bloodsport II and Bloodsport III) and a coach and a revered teacher in two others (Best of the Best and Fight to Win). He has written eleven books, produced seventy instructional videos and promoted more than 4,000 black belts over a four-decade-plus teaching career. In 2005, Cho was named the Tae Kwon Do Times’ teacher of the year, one of his many teaching awards. And then there are the magazine covers, maybe the most telling indicator of Cho’s stature in the martial arts community: He has been featured on more than fifty covers of various martial arts magazines. Only Bruce Lee has been showcased more.

Cho was born in the southern city of Pohang, in 1940. World War II was raging, and the country was in constant conflict and chaos. From a young age, Cho, the oldest of three boys, was charged with finding food for the family. He was often unsuccessful.

When he was ten, Cho, short and frail from a childhood of malnutrition, was badly beaten at a town fair by a gang of bullies. Days later, with his bruises but not his pride healed, Cho vowed to never be victimized again and joined the local tae kwon do school. The conditions were primitive and the teaching methods were decidedly old school: The young Cho, who would train five or six hours a day, didn’t receive any individual instruction. He would perform novitiate duties like washing his master’s feet, and it was an entire year before his teacher uttered a word to him. Cho and his fellow students weren’t even allowed to walk in their master’s shadow.

By thirteen, Cho had earned his first black belt. By twenty-two, when he entered the Korean army for his two-and-a-half years of compulsory service, he was so proficient at tae kwon do that he was training special forces personnel, not just in the Korean army but in the U.S. and Indian armies, too.

In 1968, Cho immigrated to the United States and settled in Chicago. He spoke very little English, and the only thing he knew about the city was the name of its onetime gangster king, Al Capone. He didn’t know much more about the rest of the country, either. But he learned quickly. After a year, he moved to South Bend, Indiana, then Milwaukee, then New York City, usually working during the day and teaching tae kwon do in the evening before spending the night at the studio. Finally, in Providence, Rhode Island, he opened a small tae kwon do school and used the last of his meager savings to take out a small ad in the local paper. A couple of days later, he had fifty students. He never looked back. Within just a few years, Cho had opened eight schools throughout New England.

Today, that number has multiplied and the Tae Kwon Do Center in Koko Marina has about 250 students. Of those, approximately eighty percent are young children. This demographic shift, a complete reversal of the composition of Cho’s student populations as recently as ten years ago, has been a phenomenon throughout the martial arts community. In addition, between forty and fifty percent of today’s students are women.

There was a time when it was unimaginable that Grandmaster Cho would be instructing the tots now found in his popular Panther class. So, how does the battle-hardened grandmaster feel about tae kwon do as after-school care? Has the transformation tarnished the tough-guy martial art? Does he pine for the days of bare-knuckled brawling?

Not at all, actually. Cho says he couldn’t be happier with the latest developments. “Tae kwon do teaches you discipline, respect and patience. This is good for children,” he continues. “I don’t miss the old days. Every child, every individual, has their own ability, and you can’t teach only one way and say, ‘If you can’t learn this, you’re out.’ Most people will never be able to jump six feet. Some can’t jump an inch off the floor. But if they leave the studio better than they started, they have enjoyed the benefits of tae kwon do...If you teach long enough, you realize that you want to pass along the spirituality, the belief that the individual can accomplish whatever they want. It’s a lifelong lesson.”